on

What Nand2Tetris Has Taught Me About Computers, and, More Importantly, About Learning

This text is about one of the greatest online courses I have taken (and I have taken many) — FromNand2Tetris constitutes a course in which you build both the hardware and software layers of a functioning computer — this journey comprises of the (virtual) implementation of the entire hardware circuitry, a compiler for a high level object oriented programming language and an operating system. Towards the end of the course you build a computer game of your choice, for instance Tetris. At this stage you will have concluded your journey of building your own computer game from Nand gates (hence the name).

If you have previously heard about this course and would like some reflection from somebody who has taken it, then this text is for you. If you really want to understand computers, maybe this text will convince you of where to start.

I often feel like it is difficult to explain — in its entirety — the genius behind Nand2Tetris. For it teaches more than the functioning of computers, it teaches about learning and about managing complexity. In the following, I will try to reason through what exactly Nand2Tetris achieves so greatly. I’ll attempt to do so, without going into the details of the course, but rather try to show you how Nand2Tetris connects the dots.

The game I created as part of the Nand2Tetris journey.

Course Motivation

Before we get to the conceptual genius of the course, let’s look at its contents and motivate why it makes sense to learn so much about computers in the first place. After all, wouldn’t you be perfectly fine simply learning the two or three scripting|programming|database languages required for your job, to the necessary degree? Probably yes, but if you want to excel at what you’re doing, Nand2Tetris constitutes the once-in-a-lifetime investment (I’m talking time-wise, as you can take the course for free). And I believe this to be true for tech people, as well as for many non-tech people, that want to effectively collaborate with a tech team.

Therefore, I will attempt to motivate the course from the perspective of a non-tech-person (again, still somebody that at least collaborates with tech-people by some means or other), as well as from the perspective of a tech-person (e.g. a software developer or web developer). I should probably mention that I myself am an industrial engineer and bring little CS background from university.

Non-tech-person perspective: It may be true that for many jobs it suffices to know how to operate some computer device or software well. However, answer the following question for yourself: Will I, at some stage in my career, have to work on a project in collaboration with a team of developers?

Be it medicine, engineering or finance, the answer is likely yes. The world is becoming more interdisciplinary every second — good communication is certainly one of the most valuable skills of the future. However, to communicate effectively, you need to learn the basic vocabulary of the language you’re trying to speak.

Now you could learn the basics of machine learning for the symptom-disease reasoning engine you’re working on, or learn about cyber security to better understand the risks of cyber attacks against your production site. However, that’s the same as trying to learn a language from nothing but a dictionary. You will lack the grammar — the structure — the big picture. Think of taking Nand2Tetris as developing your computer intuition. You won’t be a software developer after the course (far from it), but many things will make sense to you in an intuitive way. Nand2Tetris will constitute a solid foundation for any future computer related topic you tackle, and it will provide you with dozens of analogies to rely on.

Tech-person perspective: Arguably, software developers constitute the target audience of Nand2Tetris. If you already are or want to become a software developer, or can relate to that thought otherwise, imagine the following: You have established a concept and are committing it to code using some high level language like Java, Python or C++. After some time of coding, you decide that it’s time to test a specific module. Unfortunately, you encounter this really mysterious bug. Mostly through trial and error (and browsing StackOverflow) you somehow fix the bug. This might take seconds, hours, or days. However, you don’t really learn anything from fixing this bug. But then again, even bugs are logic, right?

After all, we’re talking about a machine that, in essence, comprises of logic gates. It derives that a bug must somehow be traceable to it’s origin (let’s forget about quantum effects and magic, such as electronics). The only reason why you name this weird behavior a bug is that it irritates you. You don’t understand. Yet, if you really wanted to, you could dig down to the single instruction that causes the misbehavior.

“But that requires so much knowledge!”, you might argue. “Without this specific knowledge — at the exact abstraction level at which the bug occurs — you’re not going to gain a lot from investigating bugs!”.

Fixing bugs old school.

That is right — much knowledge is required. Yet, even more importantly, you must learn to organize information in a knowledge tree and truly understand the importance of abstraction levels.

Abstraction Levels & the Great Knowledge Pyramid

If I had to summarize my greatest learning from Nand2Tetris, it would be the following:

You only truly start learning once you organize information.

This statement might seem so obvious that it fails to impress you right now. However, think about if you have ever drawn or otherwise visualized a structured tree of the things you know about a certain topic. Is this the way you “store” information? If so, that is absolutely great. After all, what is knowledge, if not organized information?

Knowledge is organized information.

So how does this connect to abstraction levels and a knowledge pyramid exactly? Naturally — being an engineer — I will attempt to illustrate this concept trough a simpler and more visual example: Let’s look at a car.

Car.

As the driver of a car, you should know how to use steering wheel, gas pedal, brakes and side mirrors. You don’t need to know how they function internally, but you must know about their use and interaction. For instance, you should know that it’s not a good idea to press the gas pedal and break at the same time. You abstract the entire car into “this thing that drives” and it becomes a black box, that you know how to use.

As a car design engineer, you need to know which modules make up a car —the car itself is not a black box to you anymore. You don’t have to worry too much about how the inner functioning of complex components such as engine or electronics system. Your abstraction level focuses more on combining these components to facilitate a car with great user experience.

As an engine engineer, you don’t need to worry about the majority of components that make up the car. Instead, you must fathom the entirety of the engine — no easy task at all — and you must know its interaction with some other car components. The car itself is a grey box (arguably, the more you know about all components of the car, the better). Most importantly though, you need to know everything about the engine.

The point of all of this: Depending on your interaction with a complex thing (such as a car — of course the same applies to a computer), you blend out everything below your current level of interest and simply treat it as a black box. You operate at an abstraction level. The driver takes the inner workings of the car for granted, the car design engineer takes the functioning of the engine for granted and even the engine engineer takes the laws of nature for granted.

However, what if you’re interested in the big picture? What if you want to understand the complex thing in its entirety — at least conceptually? Is that even possible? Without a doubt, there would be many benefits to understanding a complex thing in its entirety:

- You could easily work interdisciplinary.

- You would be able to quickly switch between different abstraction levels.

- You could learn new things much quicker.

In short, you would actually see the big picture. However, to go this step further, you must organize different knowledge pieces. This might seem absolutely obvious to you, so the real piece of information here is that you have to test this knowledge tree. Draw it! Are you 100% certain that you can recite the components and the relation of the different abstraction levels of this complex thing you’re working with?

Alright, let’s switch back to the computer. How on earth are you supposed to really understand a computer? Well, unless you want to try to pierce together and fill your own knowledge tree, I suggest you take the course Nand2Tetris.

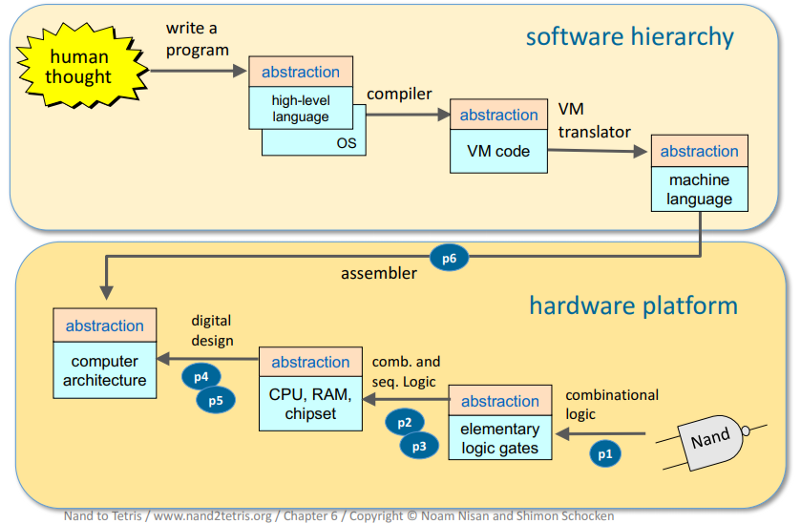

Take a look at this fantastic slide from the Nand2Tetris course.

Abstraction levels.

This is a tree of knowledge pieces. It visually connects the major abstraction levels of a computer (though this slide applies specifically to the HACK platform, other computer platforms work similarly). Your journey starts with elementary logic gates, out of which you build a chipset. You wire this chipset in an ingenious way to establish the computer architecture of the HACK platform. This computer only speaks machine language, and your next step is to write the software stack that makes it speak an object oriented high level language, as well as the Operating System that this language relies on. And voilà: Your understanding of computers just evolved from loosely connected fragments to a structured knowledge tree, with substantial knowledge about the inner workings of all components.

So that is the beauty of Nand2Tetris. You are taught, in the most systematic way possible, how the components (physical and virtual, i.e. software) of the HACK platform connect — thus creating an extensive knowledge tree. Even more impressively, you actually implement every single component yourself. Thereby, you truly understand the entire stack of the machine. Whether you want to become a software developer or work as a project manager in collaboration with a development team — you’ve developed an intuition for computer related things that would previously probably have required a degree in Computer Science.

My Coolest Bug (Yet) — Optional Read

I actually have a great example of a “bug” I encountered while writing some code in Jack (Jack is a high level Java-like language for which you write a compiler as part of the Nand2Tetris journey). Consider the following few lines of code (this is more technical, so feel free to skip — you need to understand the basics of a stack machine in order to be able to follow):

let counter = 0;

let bound = 10;

while (counter < bound + 1) {

let counter = counter + 1);

}

do Output.printInt(counter);

It turns out that this piece of code would always print 0 to my screen. Seems weird, right? I was baffled. It’s such an obviously simple code snippet, what could be wrong about it? In order to track down this behavior, I had to dive deeper into the HACK platform than the abstract Jack code would let me. Now, since I wrote the compiler and the VM translator (the HACK platform utilizes a 2-stage compilation process), I knew I could dig as deep as I wanted to — I had written all software running on the computer, and I had, virtually (pun intended), implemented its entire circuitry.

But first, let’s look at what I would previously have done to fix this “bug”. I would’ve played around. I would’ve found out, that the statement runs as expected, if I remove the +1 from the line while(counter<bound+1) , i.e. if the line became while(counter<bound) . I then would’ve found out, that I can leave the +1 in the code, if I wrap the corresponding expression into brackets, s.t. while(counter<(bound+1)). I then would have been very confused, and after some contemplating about the code, I would have moved on. The learning outcome: nil.

The learning outcome.

Why is that? The simple answer:

- I wouldn’t have known how the different components that make up the computer (mostly concerning its software stack) are connected.

- For the components I would’ve known, I wouldn’t have connected them to precise concepts — this is super important for having an intuition about where to look for errors.

So, let’s find out why the code behaved the way it did by investigating how the compiler compiles the condition of the while loop into the virtual machine code of the stack machine:

label WHILE_EXP0

push local 0

push local 1

lt

push constant 1

add

not

if-goto WHILE_END0

Notice that, at this abstraction level, local 0 corresponds to the variable counter while local 1 corresponds to the variable bound. Right away, you might notice that the less-than operation (lt) seems to compare counter and bound, and only then constant 1 is added. While that clearly seems wrong, it doesn’t fully explain the bug yet. Let’s dive deeper (note that the following explanation is HACK platform specific):

- The first three lines (

push local 0; push local 1; lt) will yield-1on top of the stack (at CPU-level everything but0represents true). - If

constant 1is then added,0will become the value on top of the stack (-1+1=0;line 6). This value is then negated and becomes-1(line 7; this negation is HACK platform specific). - At CPU-level,

if-gotoimplements aJNE(jump-not-equal) machine level instruction. So if the value on top of the stack, at the time of callingif-goto, is unequal to0, the CPU will jump to the end of the while loop, i.e. to the location corresponding to the labelWHILE_END0. If the value is equal to0, the execution of the expression(s) inside the while loop will continue and the CPU will then jump back to and retest the while-condition.

So the loop was immediately skipped, because whenever counter<bound would yield true, the subsequent push constant 1; add; would eventually yield -1 on the stack and cause the JNE machine code instruction to immediately jump to the end of the while loop.

Imagine my excitement when I simply understood, what was going on.

Arguably, this is not a terribly complicated bug. However, it vertically thrusts through several abstraction layers, making it near impossible to understand without structured knowledge.

And that’s precisely what Nand2Tetris provides you with.

Conclusion

Nand2Tetris comes with clear guidelines on how to tackle the individual projects it comprises of. Nonetheless, it certainly doesn’t constitute an easy undertaking. The entire journey divides into two sub-courses, with the first one comprising of building the hardware layer of the platform and the second, more demanding one, comprising of the platform’s software hierarchy. Consequently, the second course requires good knowledge of an object oriented high level language such as Java or Python. Depending on your previous knowledge, you might easily need 15+ hours per unit, in particular towards the end of the course (there are 12 units in total, 6 per course).

Most importantly though, you will need determination, perseverance and a fascination for what you’re doing. I personally think that the two instructors, Prof. Noam Nisan and Prof. Shimon Schocken and their team do a tremendous job at conveying the latter (just have a look at this TED-talk of Shimon Schocken about self-study, self-exploration and self-empowerment and tell me you’re not getting excited!).

Nand2Tetris won’t turn you into a software developer, system architect or electrical engineer. That’s not what it intends to do —yet, if that is what you’re seeking, it still provides an absolutely great foundation to start from and to build a university degree or numerous projects on.

Rather, Nand2Tetris equips you with structured computer knowledge. And in a world as digital as ours, it might be exactly what you need to set yourself apart.