on

About Operating Systems

I’ve recently studied (UNIX/POSIX/Linux-like) Operating Systems (OSes) and followed an excellent lecture by Prof. Chester Rebeiro. In this article I intend to summarize the main concepts behind OSes. I mainly do this as a tech-diary for myself. However, maybe somebody else may find this interesting.

As with any complex computer science (CS) topic, one could study a multitude of OS-matters for years. Any details I discuss here are hugely oversimplified — partly for readability, but mostly because I don’t understand them better myself.

OSes 101

In essence, an operating system provides abstraction. It acts as a Resource Manager, and as a means of Hardware Abstraction. As such, the OS needs to provide a common interface to a system’s resources.

The OS provides its services from kernel space. In kernel space code executes in an elevated privilege mode of the CPU that — broadly speaking — allows more direct memory and hardware access. Consequentially, the most basic OS functionality is referred to as the OS’s kernel. On top of that lie the graphical user interface and software libraries that are commonly expected to also ship with an OS.

Processes, such as Firefox or VIM, run in user space. They communicate with hardware and each other through system calls, that the operating system executes on behalf of the process.

So when you open a file in the editor VIM, VIM has no direct means of talking to the HDD to copy a file to memory. Instead, it must ask the OS to do so on its behalf.

In one sentence: From the user perspective, OSes manage your processes. Processes are programs in an execution context, i.e. when you run Firefox it becomes a process. Processes themselves may split into smaller units, called threads — we will not go into the details of threads, other than that threads share common memory (namely that of their parent process), whereas processes have their own memory.

If all OS services run in kernel space, the kernel is said to be monolithic. If, one the other hand, the kernel only provides the absolute necessities (Inter-Process Communication, Virtual Memory and Scheduling) and bundles other functionality (networking, drivers etc.) in user-space applications, the kernel is referred to as a microkernel.

What Goes Into an OS?

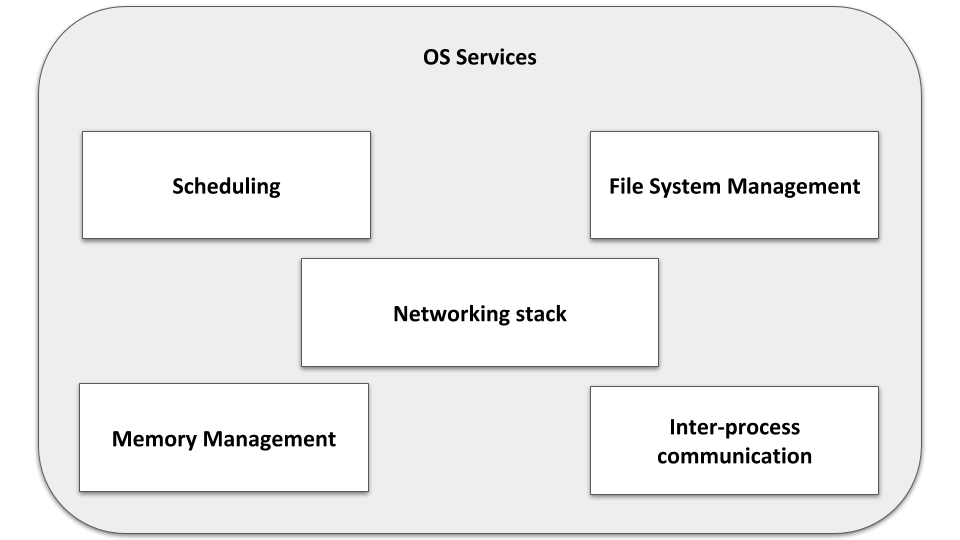

Any modern operating system provides the following services:

OS services of modern-day operating systems.

Let’s look at these in a little more detail:

Memory Management

The OS provides user processes with access to system memory — this is where the code and data of any program is copied to from a storage device (such as a hard disk, SSD, etc.), before it can be executed. Through techniques known as Paging and Segmentation, every process receives its own Virtual Memory. This means that any process acts as if it has all system memory to itself. Unless explicitly agreed upon, it cannot access any other process’s memory. Paging, in principle, is not all that complicated, I refer the interested reader to this video.

Of course sharing data between processes is sometimes necessary — processes may share data through files, shared memory and other mechanisms. Linux pipes, for instance, allow shared data between parent and child processes (to connect stdout of the parent to stdin of the child).

CPU Scheduling

Have you ever wondered why, even on a single-core computer, everything behaves so, well, simultaneous? Why can you press your keyboard and move the mouse — at the same time — and see results on your screen immediately? While true concurrency is achieved on multi-processor systems, having multiple processors is no necessity in fooling you to believe that your system runs processes concurrently. Of course, a single-core system doesn’t. It simply switches process- | thread-context at a high frequency, depending on whether some process | thread requires real-time behavior (which usually means that it’s I/O heavy) or not. This process of quick context switching is referred to as scheduling. Different scheduling algorithms may be implemented to switch contexts according to different metrics.

One core concept of a scheduler is to prevent starvation (a certain process never executing) and to implement priority (i.e. acknowledging that certain processes are more real-time-sensitive or resource intensive than others).

File System Management & Device Drivers

Access to caches and RAM is very low-level and baked into hardware and the core of the OS. Access to the persistent storage (HDD, SSD, etc.) — and to connected devices in general — brings us to file systems and drivers. In order to abstract away hardware-specific details, Linux supports an application programming interface (API) called virtual file system (VFS), that allows any userland process to access files on a file system in the same fashion. For this reason, I can plug in a (NTFS-formatted) USB stick into my computer and copy files to my ext4-formatted SSD using the shell:

cp /media/sean/231154463AF780E7/projects /home/sean/

Think about what happens here. I’m just using a system call — under the hood a myriad of device drivers, file system drivers and operating system specific functions take care of reading and copying the data from different hardware devices (which happen to use different file systems). That is why device drivers live at the kernel layer — they glue together hardware and system calls, and thus hardware and userspace.

It’s interesting to note that contrary to a driver, Firmware runs directly on a hardware device. I think of Firmware as (low-level) software, that acts like an interpreter to I/O commands issued by the OS to a device. Take a SSD for instance: It has a built-in microcontroller, which nowadays could be something of a System on a Chip, i.e. an entire computer on an integrated circuit chip! Consequentally, the SSD Firmware could be seen as an Operating System for the SSD itself. Talk about complexity!

Let’s visualize these different abstraction layers, by going through what might happen when we read from a hardware device, e.g. an air quality sensor connected to the computer via a serial interface.

Userland perspective

From userland perspective, we use system calls. In Linux, we would first use the open system call to receive a file descriptor, and then use the read system call to read from that file.

# obtain a file descriptor; ask for read permissions and file in binary mode

fileDescriptor = open('fileName', 'rb')

# read first 10 bytes of file

data = fileDescriptor.read(10)

# print the data to stdout

print(data)

High-level OS perspective

From a high-level OS perspective, information bubbles down until it reaches a device driver that talks to the hardware directly. Hugely oversimplified, system calls may function something like this (pseudocode):

def open(fileName, flags):

callingProcess = getProcessContext()

if (checkUserPermissions(fileName, flags, callingProcess)):

addFileToSystemFileTable(fileName, callingProcess)

fileDescriptor = createFileDescriptor()

return fileDescriptor

else:

return 0

def read(fileDescriptor, size):

# look up driver that handles specific fileDescriptor

driver = lookUpDriver(fileDescriptor)

# call driver's function

data = useDriverToRead(driver, fileDescriptor, size)

return data

Notice that the OS is in charge of checking user permissions and is keeping track of open files. It then delegates reading the data to a driver.

Driver perspective

From the driver’s perspective, things may look like this:

def read(fileDescriptor, size):

command = craftCommand(size) # command to send to Hardware

protocolDriver = getProtocolDriver() # get driver that handles next

# abstraction layer

# use this driver to get the data: note that this driver may use

# further drivers

data = useProtocolDriverToSendCommand(protocolDriver, command)

return data

A protocol driver may wrap the device command. This data may then be processed and wrapped once again by other lower level drivers. Eventually, the data is handed to some BUS controller, from where it is sent to the sensor.

Firmware perspective

So where does firmware come into play? Remember that we previously established that Firmware runs on the I/O device itself. Thus, firmware may be running on the sensor. Maybe, the sensor does something along these lines:

def main(noDataPoints):

startFan() # start the fan to get air flow

wait(10) # wait for 10 ms to get fan running

for i in range(noDataPoints):

datapoint = readDataPoint() # read a datapoint

sendViaBus(datapoint) # send it via the bus

return

So the logic is the following: The user uses the OS system calls. The OS calls into its driver(s). The driver(s) rely on the firmware of the sensor to execute the command that they issue. If there is a binding contract between every abstraction layer, everything works. Note that in reality, these contracts are very complicated.

Networking Stack

Arguably, the networking card is only yet another device, with corresponding drivers. However, in an OS context it often gets mentioned as a separate unit — for networking is an essential part of any modern computer setup. A (once again, hugely simplified) explanation of how Linux handles incoming packets looks like this:

- The corresponding driver (which is network card specific) is loaded and initialized. This happens once, at the setup stage. The driver may register interrupt1 handlers, to deal with interrupt requests (IRQs) issued by the network card.

- A packet arrives at the network card.

- Usually, the network card will have negotiated direct memory access (DMA) with the OS. It can therefore copy data directly to memory, without going through the CPU.

- After copying is finished, the network card will generate a hardware interrupt, to let the CPU know that it should process the packet (alternatively, the OS could periodically poll the data).

- Either way, further kernel processing bubbles up the information and passes the information to protocol layers.

- Finally, the kernel provides the data to OS-clients (userland processes) as sockets. From here on applications take care of the data and protocols above themselves.

Altogether, this process once again relies on a multitude of interfaces working together. It is worthwhile to note the difference between receiving from a device, in which case information bubbles up to userland, and sending to a device, in which case information bubbles down to the device.

Inter-process communication

Lastly, an OS must provide means of communication between processes. I mentioned this previously with UNIX pipes. If efficiency becomes important, shared memory, signals and sockets can be used. The purpose remains the same: To allow processes to communicate with each other.

With inter process communication comes the great task of synchronicity. If two processes share a resource, such as a part of memory, the processes must ensure that they access shared memory in an agreed upon manner, that prevents errors from happening. Mostly, this happens through the use of spinlocks, mutexes and semaphores. I might write another article about these at a later stage.

Summary

From the user’s perspective, OSes provide a clear and concise interface to interact with the computer. Behind the scenes, however, the OS must manage a myriad of different resources that may not function similarly, at all.

While internet resources on OSes are great and abundant, different abstraction layers are often not connected in an understandable way. This makes it near impossible to understand a higher-level behavior in its entirety, without spending a considerable amount of time researching all involved layers. After having spend some time trying to grasp OSes, I ended up with Andrew S. Tanenbaums book Modern Operating Systems. I have come to the conclusion that, despite great resources on the internet, it’s much easier to follow the thoughts of one or two experts that understand the matter to the highest degree possible. Once abstraction layers become clearer, switching the specifics becomes easier — I recommend the introduction alone to anyone interested on the matter.

-

An interrupt is a way for I/O devices to force the CPU to first process an interrupt request, before continuing with its work. As you may guess, interrupts are a study for themselves. To schedule processes, for instance, the CPU relies on timer interrupts. I recorded a video showing real-time timer interrupts on my computer, to give you an idea of the number of interrupts we’re talking about (Linux makes interrupts available under

/proc/interrupts): ↩︎